Federal Income Tax: Capital Gains Tax

Students: the CFP wants you to understand all aspects of the capital gains tax and how to apply in common situations. Make sure you pay attention to dates, filing status, rates, and what the specific test question is asking for!

Individuals: a lot of times we don’t think taxes on investments are a big deal. As your investments grow the taxes are a HUGE deal! You’ll wish more and more that you took advantage of Roth contributions as well as understood that capital gain on taxable investments will impact your future investing decisions as you may see yourself “pinned down” by the unrealized tax liability.

Advisors/Professionals: you MUST understand how your investment recommendations affect a client’s tax liability. Capital gains taxes are often misunderstood and it is one of the COMMON reasons why a client will leave an advisor (bad ancillary advice on taxes or recommendations that caused adverse taxation)

What is Capital Gains tax?

Capital gains occurs when you sell a “capital asset” (or an asset treated as such for taxes) at a gain. To go over a few basics…

(note** on this page most examples will be of invested assets such as a stock, ETF or mutual fund in a taxable account)

Your “holding period” describes how long you’ve owned the asset(s).

The “gain” is relative to your purchase price (cost basis) plus any adjustments (+/-) to your original cost basis.

Your basis changes based on costs to acquire/dispose the asset as well as any adjustments along the way.

For stocks - the share price + commission paid or transaction costs (if any) is your “original cost basis.” When you sell, the commission paid or transaction costs (if any) adds to your cost basis (or reduces the sale price - how ever you want to view it).

For real estate or other assets - you might have depreciation deductions or improvements or losses that adjust your cost basis over time (much more complicated).

We describe gain as either “realized” or “unrealized” - gain is “unrealized” until the asset has a triggering event (typically “sold”). Capital gains tax only applies to REALIZED gain. On a taxable investment account, you’ll note that there is a grid for unrealized and realized short term and long term gains and losses. See example (below) from a sample taxable investment account statement:

You can also have a “loss” on your assets and if you sell the asset(s) they are now “realized losses” and will offset any realized gain in the same tax year.

Note: typically your different types of income are in “silos” where you can’t apply net capital loss from investments to earned income - but there is a small yearly exception! You can apply a net loss of $3,000 against other income (single or MFJ). Any further loss is allowed to be carried forward - applying to offset net gain in future years (first) and again allowing $3,000 of loss per year against future income.

Short Term Capital Gains/Loss - asset(s) sold within 12 months

Short term gain is taxed at your normal ordinary income tax rates which translates to your highest marginal bracket(s).

Long Term Capital Gain/Loss - asset(s) sold after 12 months (literally “12 months and a day")

NOTE CFP STUDENTS - they will try and trick you by saying “John bought stock on Jan 15 and sold it on Jan 15th the following year. This is considered SHORT TERM as it would need to be held till at least Jan 16th before being LONG TERM.

WHAT ABOUT LEAP YEARS? Tricky Tricky… Yes leap years require an additional day of holding (366 days) which is why we typically say “more than a year” and not “more than 365 days.” The CFP test will NOT try and trick you this way but personal investors should understand this!

Example from a sample investment account statement showing “realized and unrealized” short term and long term gain/loss.

Long term capital gain is taxed at a special “long term capital gain” (LTCG) tax rate which corresponds to your TAXABLE INCOME. Based on your other calendar year income, the LTCG “sits on top” or “stacks” on your taxable income. For many years the LTCG tax rate was just a flat “15%” but there are now actually three distinct tax rates. Secondly, when they revised the LTCG tax rates they matched the 1st/2nd brackets the first year but then didn’t index the same in future years. It is common for us to say “those in the first two brackets are taxed at 0%” but technically the LTCG and ordinary income tax brackets are slightly off (see below). There is also an additional tax on investment income called the “net investment income tax” (or NIIT) that applies to those with higher income/gains and can add 3.8% tax - so we sometimes call this the “4th bracket” of LTCG as you could get taxed 15%+3.8% or 20%+3.8% (in fact most all that would be taxed at 20% will automatically get bumped to the 23.8% tax rate). More on the NIIT in another section!

2021 LTCG brackets

MFJ (married filing jointly)

0% rate = $0 - $80,800 taxable income

15% rate = $80,801 - $501,600 taxable income

20% rate = $501,601+ taxable income

Single

0% rate = $0 - $40,400 taxable income

15% rate = $40,401 - $445,850 taxable income

20% rate = $445,851+ taxable income

Head of Household

0% rate = $0 - $54,100 taxable income

15% rate = $54,101 - $473,750 taxable income

20% rate = $473,751+ taxable income

There are also some different rates for a couple different types of property held long term.

Collectibles (antiques) or Section 1202 stock = maximum rate of 28% (or your marginal bracket if less, IE 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%)

Depreciable real estate (depreciation recapture tax) = maximum rate of 25% (or your marginal bracket if less, IE 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%)

Examples of how the LTCG tax applies

Single filer, $30,000 of taxable income for the current year. Has $10,000 of LTCG in addition.

$30,000 of taxable income puts the single filer in the top section of the 2nd (12%) tax bracket.

Adding the $10,000 = $40,000 of taxable income. Now apply the LTCG tax brackets! In this case, all of the added LTGC is under $40,400 so the LTGC tax applied would be 0%! (no additional tax owed).

Single filer, $30,000 of taxable income for the current year. Has $20,000 of LTCG in addition.

$30,000 of taxable income puts the single filer in the top section of the 2nd (12%) tax bracket.

Adding the $20,000 = $50,000 of taxable income. Now apply the LTCG tax brackets! In this case, some of the added LTGC is under the $40,400 (0% tax threshold) and some is over so we must apply accordingly:

From $30,000-40,400 = $10,400 of the gain = 0% tax

From $40,401-$50,000 = $9,599 is in the 15% LTCG tax bracket. $9,599 x 15% = $1,439.85 in LTGC tax

CFP STUDENTS - make sure you answer the “right” question! Were they asking for total tax liability (ordinary income + LTGC tax), just the LTCG tax, or were they asking a different question such as “how much of the gain is exposed to tax” (in this case = $9,599).

Note = using this example, many would believe that because the single filer was in the 2nd tax bracket they don’t have to pay ANY LTCG tax on ANY amount of LTGC. This is NOT true as the LTCG sits or stacks on the existing taxable income and only the amount under the threshold(s) apply to the 0% (or lower) rates.

LTCG is part of your federal 1040 and despite carrying its own (lower) rates, does impact your gross income, AGI, and taxable income figures on your federal taxes. Many (falsely) believe that because the LTGC tax is a “separate tax system” that it doesn’t interact with your regular income tax and this isn’t true! While LTCG tax is calculated separately and doesn’t increase your ordinary income tax (or adjust you up ordinary income brackets), the amount of LTCG does add in to your AGI! This is VERY IMPORTANT to understand as we know how important AGI is. Many think because they aren’t paying tax on the LTCG (0% rate) that it doesn’t impact their AGI - it does add to it and could disqualify those with lower incomes from state/federal aid or other programs/subsidies/credits. For those with higher AGIs it could affect your student’s financial aid, tax credits, or Roth IRA contribution eligibility (or stimulus check amounts in 2020 for instance).

Example chart (from Kitces website - article linked below) of how a married (MFJ) filer with AGI of $60,000, reduced by $24,400 standard deduction (2020 rate) has “taxable income” of $35,600. Then adding $60,000 of capital gains “stacks” on top of the taxable income. What it also doesn’t go back to show is that in this case the person’s AGI would also now be $120,000 (despite only a minority portion of the capital gains being exposed to tax).

Qualified Dividends

Qualified Dividends are dividends from domestic corporations (or foreign corporations incorporated in the US that pay US taxes). While ALL dividends are taxed yearly (regardless if they are reinvested or not), you have the special election with Qualified Dividends to have them taxed at the LTCG tax rate (and not one’s marginal ordinary income tax bracket rate). This can be a major tax savings! Why did the IRS/gov’t do this? It has to do with the double taxation of C corporations (because the shareholders then pay tax at their own tax rates) so it applies some relief to the overall tax burden!

Obviously when you own individual stocks, it is easy to follow if the company dividends should be treated as “qualified.” But what about from mutual funds or ETFs? Do dividends from these receive special treatment? YES!! (well - for the applicable portion) Typically US/domestic funds/ETFs have the vast majority of their dividends as “qualified dividends” (typically 95-99%). Many larger-company developed international funds will still have a majority of dividends as qualified (sometimes 50-80%) while mid/small-cap international and/or emerging market funds might have less (sometimes 30-60%).

Keep in mind this only applies to STOCK dividends and not corporate bond coupons (yield) which sometimes looks the same when being paid out of mutual fund distributions as monthly/quarterly dividends. Many “balanced funds” hold corporate bonds (and other bonds) and this income does NOT receive the special LTCG “qualified” treatment.

Holding period - it isn’t your typical “over one year” holding period for qualified dividends. We’d commonly say you must own the stock/fund at least 2 months but here are the actual rules:

Mutual Funds/ETFS - you must hold the applicable share of the fund for at least 61 days out of the 121-day period that began 60 days before the fund’s ex-dividend date

Stock(s) - you must have held those shares of stock unhedged for at least 61 days out of the 121-day period that began 60 days before the ex-dividend date.

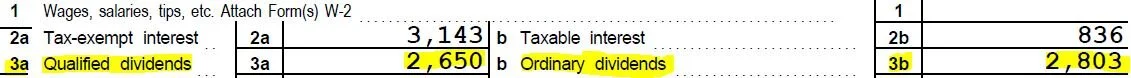

Tax reporting - qualified dividends appear on the front page of your 1040 as part of gross income but it can appear a bit confusing…

ALL dividends (including qualified) are reported in Box 3b on your 1040.

Qualified dividends are report in Box 3a on your 1040.

This means 3b must ALWAYS be greater than 3a. If you are just glancing over the federal 1040 you wouldn’t catch that 3b includes the amount of 3a. For those in a lower tax bracket, this means you might have $4,000 in 3a and $4,200 in 3b… While first glance makes it seem like you have $8,200 in taxable dividends; YOU DON’T! You have $200 in ordinary dividends and $4,000 in qualified dividends. If you are below the 15% LTCG threshold that’d mean that your qualified dividends aren’t taxed! (only the $200 of ordinary dividends would be taxed at your marginal ordinary income tax rate)

See actual example below

More info

Example of a 1040 form with the boxes filled in with dividend amounts. Note that $2,650 is INCLUDED in the $2,80 of “ordinary dividends” so the TOTAL dividends is $2,803 (with $153 actually being “ordinary” and the remainder is “qualifed” of $2,650)

Any practical suggestions for real world application?

Why yes, I’m glad you asked! There are a number of practical take-aways and tips/tricks. Below are the BASICS though each one would need to be explored more in depth.

If you are in the 1st/2nd tax bracket (and would have room for “0% capital gains”), try “harvesting” your gains over a number of years where they all fall under the 15% threshold so you don’t have to pay the tax!

Make sure you are paying attention to your AGI (and related items - FAFSA, credits, Roth IRA contribution limits, stimulus check thresholds, federal/state aid eligibility) when you add a large chunk of capital gains on any specific year.

Asset location - if possible (holding multiple “types” of accounts), place more of your ordinary dividend funds (and taxable bond funds) inside your traditional IRA/401k. These might include international funds, REITs, and taxable bond funds. Place funds/stocks with qualified dividends (or no dividends!) in your taxable investment accounts so you receive the preferential capital gains tax treatment (on growth and qualified dividends).

Capital assets receive a “step up in basis” at death so any stocks/funds that you held inside a taxable account will be “income tax-free” at death to the beneficiary! (more on this in estate planning section)

You can donate your appreciated stock/funds/real-estate (or other capital assets) DIRECTLY to a non-profit organization and not pay ANY capital gains tax and receive a full itemized tax deduction for the amount transferred. (more on this in the charitable giving section).

Be careful buying/selling funds in a taxable investment account. Try and choose funds that you can “buy and hold” for long periods of time. Also make sure you are choosing funds that are tax efficient and don’t “spit out” high yearly forced capital gains distributions (from the active management trading). Index funds are great as you don’t have to worry about future fund manager performance and they typically don’t have much for yearly forced capital gains distributions!

Remember even if you sell fund XYZ and buy fund ABC (inside the same taxable account) that is a TAXABLE transaction on the year!!! You might argue “but I didn’t liquidate or move cash from the account!!” BUT it doesn’t matter! Taxable transactions happen inside the account and are taxed in the year executed! If you do decide to be more “active” with some of your investments, consider doing so inside your qualified plan(s) or IRAs (traditional or Roth) as the buys/sells/dividends don’t trigger any taxation (until you remove funds from the account).

Tax-Loss Harvesting: you can offset gain with losses. If you have a bond fund that is showing an “unrealized loss” (likely due to interest rates going up and the fund value going down), you could sell this and buy a similar bond fund, generating a current year loss, which might offset your current year gain from a dividend, capital gains distributions, or sale of stock(s)/fund(s).

Pay estimated tax payments during the year for the estimated tax liability on your net realized capital gain. Taxable investment accounts typically don’t have any federal/state withholding abilities so you might want to double check with your CPA/tax-preparer on paying any amounts to the fed or state during a year with larger realized capital gains.

Most taxable investment accounts will automate tax reporting and elect FIFO (first in, first out reporting method) for stocks/ETFs/securities and “average cost basis” method for mutual funds. This may make small differences on decisions on what to sell, donate, etc…

You might also decide, if actively contributing to the taxable account, to change up your investments so you have similar funds/investments with different tax history (cost basis). This might allow you more flexibility later on with tax-loss harvesting, rebalancing, or other decisions. For instance, if you have a Vanguard S&P 500 fund with 50k in cost basis and 80k in unrealized gain; you could make future contributions to a Fidelity S&P 500 fund and it would generate higher cost basis on the same asset (since new contributions are made at the higher share prices). If the market then dipped 10%, you could “tax loss harvest” from the new Fidelity fund (loss) while leaving the Vanguard fund alone. Or maybe you donate to your church and donate some of the Vanguard fund while making new contributions to the Fidelity fund.